Rebounding (an exercise technique involving jumping on a mini-trampoline) is often marketed as “low impact.”

However, it can still place stress on the joints, risk injury to the soft tissues, and challenge safety for those with poor balance.

There are also risks for people with chronic joint issues, a weak pelvic floor, osteoporosis, uncontrolled blood pressure, or any other complex health issues.

Poor-quality equipment or failing to obtain medical clearance can also complicate things.

Common issues with rebounding include:

While risks are manageable for some users with the right setup and guidance, others may be better served by a steadier, safer, and equally effective option, such as speed walking or Whole Body Vibration (WBV).

Not inherently.

Rebounding exercises are often described as low impact because the trampoline absorbs some landing force.

However, while the surface reduces peak ground reaction forces compared with hard ground, rebounding still involves repeated loading, balance challenges, and vertical acceleration.

For some people, this can trigger negative side effects or injuries.

Understanding that most rebounding side effects are related to load and repetition rather than the equipment itself.

When clinicians talk about the negative side effects of rebounding, they’re not just referring to post-workout fatigue.

They usually mean:

| Factor | Rebounding | Speed Walking | Cycling | Vibration Plate |

| Joint load | Moderate | Low | Low to Moderate | Low |

| Balance demands | High | Low | Low to Moderate based on outdoor or indoor | Moderate to High |

| Fall risk | Moderate to High | Low | Low to Moderate | Low |

| Space | Minimal-Moderate | Minimal | Minimal to High based on outdoor or indoor | Minimal-Moderate |

| Medical clearance | Commonly advised | Rare | Commonly advised | Commonly advised |

Most negative side effects of rebounding exercises show up early, often within the first few sessions—especially if intensity, balance demands, or joint load are underestimated.

These usually settle within a few sessions.

If you experience these symptoms, it’s important not to “push through” them.

Joint pain after rebounding is common and usually mechanical.

The most frequent contributors include:

Joint symptoms: adjust vs discontinue;

| If You Notice… | Adjust | Discontinue |

| Mild knee or ankle ache after sessions | Lower bounce height, shorter sessions, softer knees | Pain walking and squatting |

| Hip or low-back stiffness | Check stance width, slow tempo | Sharper pain, catching, or pain beginning to radiate down the leg |

| One-sided discomfort | Reduce intensity, reassess alignment | Spreading of unilateral pain to other areas |

These symptoms are often mislabeled as “detox,”

but there are more plausible explanations:

Yes—especially in people with existing spinal conditions, poor bounce mechanics, or a low tolerance to repeated vertical loading.

Every bounce creates vertical loading that travels from the feet through the ankles, knees, hips, and pelvis and into the lumbar and thoracic spine.

While the trampoline mat absorbs some force, it also rebounds energy back into the body, requiring the spine and surrounding muscles to repeatedly decelerate and restabilize.

It helps to distinguish between two very different sensations:

This depends on an individual’s physical fitness and underlying health conditions.

Rebounding is clearly contraindicated when:

Sciatica involves irritation or compression of a spinal nerve, often causing pain, tingling, or numbness that travels into the buttock or leg.

Because rebounding places repeated vertical load through the spine, it can easily aggravate nerve-sensitive conditions.

If bouncing increases leg pain, tingling, or numbness, rebounding should be avoided.

In a small number of cases where symptoms are mild and stable, a carefully supervised trial using very small, controlled bounces may be considered,

but only with guidance from a qualified clinician who understands the individual’s spinal presentation.

Scoliosis creates asymmetrical loading patterns in the spine, meaning one side of the back often absorbs more force than the other.

Rebounding can exaggerate these asymmetries, particularly if balance or bounce mechanics are uneven.

As a result, pain is one-sided or progressively worsens.

Here, rebounding is generally not advised.

In some situations, clinicians may permit very gentle, symmetrical loading under close supervision,

but tolerance varies widely, and many people with scoliosis find rebounding uncomfortable or unpredictable.

Degenerative disc disease reduces the spine’s ability to absorb and distribute shock.

As a result, activities involving repeated compression and decompression—such as rebounding—are more likely to provoke symptoms.

If back pain flares with impact or vertical loading, rebounding is typically poorly tolerated.

Many people with DDD report that rebounding aggravates symptoms rather than improves them, making steadier, lower-load forms of exercise a more suitable option for managing long-term back comfort.

Common stress responses and “red flags” to watch for when rebounding with back or nerve sensitivity.

Stop rebounding and seek medical advice if you notice:

These symptoms suggest serious injury, not just exercise-related soreness.

Each bounce creates downward pressure through the abdomen and pelvis.

On landing, the pelvic floor must rapidly contract to counter gravity, support the bladder and bowel, and maintain continence.

This happens repeatedly—often dozens or hundreds of times per session.

Pregnancy, childbirth, abdominal surgery, hormonal changes, or prolonged sitting can reduce the pelvic floor’s ability to respond quickly and strongly.

When that support system is already stretched or fatigued, rebounding amplifies the load rather than training it safely.

Jumping does not usually cause prolapse on its own, but it can trigger symptoms or worsen an existing prolapse.

Prolapse occurs when pelvic organs drop due to weakened or overstretched support tissues.

Rebounding increases intra-abdominal pressure and downward force, which can push against already vulnerable structures.

This is why people with known prolapse or early symptoms such as heaviness or bulging are at higher risk of symptom flare-ups during rebounding.

Leakage during rebounding is commonly due to stress urinary incontinence, which means urine escapes when pressure rises suddenly, such as during coughing, jumping, or bouncing.

It’s not simply about muscle strength; timing, coordination, and endurance are important.

If the pelvic floor can’t contract fast enough to counter the impact of each bounce, leakage can occur—even in people who otherwise feel strong.

This is a clear signal that the current load exceeds what the pelvic floor can manage safely.

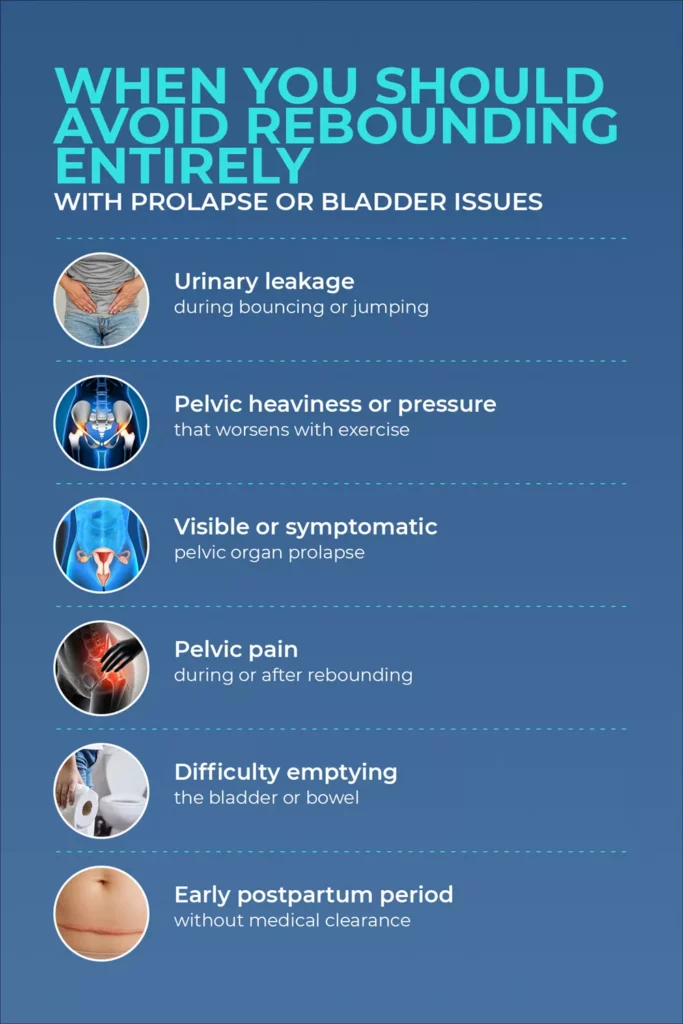

Key warning signs indicating when to pause rebounding exercises due to pelvic floor or bladder concerns.

Rebounding should be avoided if you experience:

In these situations, continuing to rebound can reinforce strain rather than recovery.

A pelvic floor physiotherapist can assess readiness, guide safe progression, and recommend safer, symptom-appropriate alternatives.

For some people, rebounding feels easier than running; for others, it becomes a fast track to joint flare-ups—especially in the knees, ankles, and hips.

Mini-trampolines reduce the hard impact you’d get from landing on concrete, but they also change how forces are absorbed and returned.

The mat stretches downward and then recoils, meaning joints must control both deceleration and rebound.

This increases demand on stabilizing muscles and joint sensors (proprioceptors).

For healthy joints, this can feel springy and comfortable.

For joints with reduced cartilage, poor alignment, or prior injury, the repeated loading and instability can increase irritation rather than reduce it.

Rebounding is not automatically unsafe for people with knee issues, but it can be when symptoms are already active.

Some people with mild knee arthritis tolerate very low-amplitude, controlled bouncing—especially if sessions are short and pain-free.

However, rebounding is a poor choice when knees swell after activity, feel unstable, or hurt during everyday tasks like climbing stairs or moving from sitting to standing.

In these cases, the repetitive compressive and shear forces can aggravate joint surfaces rather than support them.

Ankles and hips often become the weak link during rebounding.

The unstable surface challenges ankle control, which can reactivate old sprains or create new strain if the joint rolls repeatedly.

At the hip, poor control or fatigue can lead to excessive inward or outward movement, increasing stress on surrounding tissues.

People with a history of ankle sprains, hip impingement, or balance issues are more likely to notice pain or instability early on.

One bad session doesn’t usually cause lasting damage.

The concern is patterns over time.

Warning signs include joint pain that lasts more than 24–48 hours, swelling that increases week to week,

stiffness that worsens rather than improves, or a gradual loss of tolerance to the same workout.

These are signals that joint tissues are not adapting well.

Ignoring them and continuing to rebound at the same intensity is how short-term irritation can turn into longer-term joint problems.

Rebounding is sometimes promoted as bone-building and senior-friendly, but fracture risk depends on bone density, balance capacity, vision, reaction time, and fall tolerance.

Osteoporosis reduces bone strength and the ability to tolerate sudden or uneven loads.

While controlled, weight-bearing exercise is important for bone health, rebounding adds vertical acceleration and balance challenges at the same time.

For people with established osteoporosis or a history of fragility fractures, the risk is not the bounce itself but loss of balance, which can lead to falls that result in wrist, hip, or spinal fractures.

Evidence-based osteoporosis programs typically prioritize predictable loading and fall prevention over unstable or reactive surfaces.

Age alone doesn’t make rebounding unsafe, but several age-related factors change risk.

Balance responses slow, vision may be less sharp, reaction time decreases, and bone density often declines.

Together, these increase the consequences of a misstep.

Some older adults with excellent balance and normal bone density may tolerate rebounding very well.

Vertebral compression fractures are common in osteoporosis and often occur with minor stress rather than major trauma.

Repeated spinal loading, sudden flexion, or abrupt changes in force can increase risk, particularly in the thoracic and lumbar spine.

These fractures may not cause immediate severe pain but can lead to height loss, chronic pain, and posture changes over time.

Activities that involve unpredictable spinal forces deserve extra caution in people with known low bone density.

Rebounding is often promoted as a one-size-fits-all wellness tool, but people with medically complex conditions need to be more cautious.

For vascular, lymphatic, cancer-related, and neurological conditions, medical guidance is important.

Healthcare professional reviewing medical clearance documents in a clinical environment.

Rebounding is often prescribed as good for circulation because repeated muscle contractions act as a muscle pump, which may help venous return and lymph movement.

However, these same forces can increase pressure and strain in already compromised systems.

With varicose veins, prolonged or vigorous bouncing may worsen aching, heaviness, or swelling.

In lymphedema, uncontrolled or high-intensity rebounding can aggravate swelling rather than relieve it, particularly without compression or specialist oversight.

For people with high or unstable blood pressure, rapid movement changes and sudden stops can provoke dizziness or blood pressure fluctuations.

While some individuals may tolerate short sessions, these conditions warrant explicit medical clearance and careful symptom monitoring before rebounding is considered.

There is no evidence that movement or rebounding “spreads” cancer.

Physical activity is generally encouraged during and after cancer treatment when appropriate.

However, rebounding may still be unsuitable during certain phases of treatment due to fatigue, low bone density, neuropathy, balance issues, surgical recovery, or active lymphedema.

Oncology teams often recommend low-risk, predictable movement tailored to the individual rather than unstable or high-demand activities.

The key factor is not cancer itself but the side effects of treatment and overall physical resilience.

Neurological conditions can significantly change how the body responds to rebounding.

People with seizure disorders, severe balance impairment, peripheral neuropathy, or spasticity may be more vulnerable to falls, symptom provocation, or loss of control on an unstable surface.

Rebounding can also overstimulate sensory systems, making it poorly tolerated in some neurological presentations.

In these cases, bouncing is often more risky than beneficial.

If any of the following apply, rebounding should be paused or cleared with a qualified clinician (physiotherapist, pelvic health specialist, or physician):

Before starting rebounding with a medical condition, bringing clear questions to an appointment can help guide safer decisions:

Use a stable, level surface with enough clear space around the rebounder.

Wear grippy footwear, and use a support bar if you’re new, older, or managing a health condition.

Keep bounces small and controlled with soft knees and a neutral spine.

Focus your gaze forward to support balance, and avoid high jumps, twisting moves, or fast direction changes that increase joint and spinal load.

Start with very short sessions (1–2 minutes) at low intensity, once a day or every other day.

Increase duration slowly only if symptoms do not worsen within the following 24 hours.

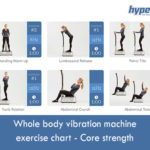

A guide to low-impact physical activities that offer predictable loading for those with joint or pelvic health concerns.

It’s time to move on from rebounding if you’ve adjusted the setup, reduced bounce height, and shortened sessions, but symptoms still flare or worsen.

Exercise only works when the body can recover and adapt.

If rebounding repeatedly pushes you into setbacks, switching approaches is a smart decision.

Different conditions call for different types of load and control:

If you’re comparing equipment at the decision stage, focus on risk control:

Hypervibe’s approach prioritizes mechanical stimulus with low impact, supported by conservative protocols that clinicians can understand, adapt, and supervise.

The focus is on controlled exposure, adjustable loading, and safety.

This makes the equipment easier to integrate into rehabilitation, chronic condition management, and long-term movement plans—where safety and consistency are critical.

Rebounding does not usually cause joint damage from a single session, but problems can develop when pain, swelling, or stiffness persists over weeks. Repeated vertical loading on an unstable surface can aggravate knees, ankles, or hips that already have arthritis or prior injury. If joint symptoms last more than 24–48 hours or worsen over time, stop rebounding and talk to a clinician. The most common issues include ankle sprains, knee irritation, low-back flare-ups, and falls due to loss of balance. Pelvic floor symptoms such as urinary leakage are also frequently reported, especially in women. If injuries or near-falls occur, a physiotherapist can help assess whether rebounding is appropriate for you. Rebounding can cause rapid changes in heart rate and blood pressure, particularly when starting or stopping suddenly. Some people with well-controlled blood pressure may tolerate gentle, short sessions, but those with uncontrolled or labile blood pressure should be cautious. Always speak with your doctor before rebounding if you have cardiovascular concerns. Yes, rebounding can worsen symptoms in these conditions by increasing spinal loading, downward pelvic pressure, or venous strain. While rebounding does not usually cause these conditions, it can trigger symptom flare-ups. If you have any of these issues, consult a pelvic health physio or medical professional before trying rebounding. Rebounding may suit people with good balance, healthy joints, no pelvic floor symptoms, and no significant medical conditions. Even then, benefits depend on conservative technique and gradual progression. If you’re unsure whether you fit this group, a clinician can help you decide. For many people—especially those with joint, balance, or pelvic floor concerns—a vibration plate is often safer because it avoids jumping and allows controlled posture and intensity. Rebounders introduce greater balance and fall demands, which increase risk for some users. A physiotherapist can help you choose the option that best matches your health profile. Yes. Dizziness, sharp pain, pelvic symptoms, or loss of balance are warning signs rather than normal adaptation. Stop the session and speak with a healthcare professional if these symptoms recur.

Rebounding is often described as low impact, but its side effects are highly individual.

Joint pain, pelvic floor symptoms, balance issues, dizziness, and flare-ups of existing conditions are signals to reassess—not push through.

For people with back pain, arthritis, osteoporosis, pelvic floor concerns, neurological conditions, or a higher fall risk, rebounding can place more strain than benefit on the body.

A Vibration Plate may be a safer alternative when you want movement and stimulation without jumping, landing, or unpredictable balance demands.

With adjustable settings, supported stances, and clearer clinical guidance, vibration platforms are often easier to use consistently—especially for medically complex or cautious users.

If you’re deciding between options, Hypervibe’s Buyer’s Guide helps explain what to look for in Vibration Plates, while the Hypervibe product range focuses on evidence-aligned design and clinician-friendly protocols for safer home use.

Updated on: 08.09.2021 The lymphatic system is involved not only...

Stress can make you gain weight – we’ve heard this...

Various theories exist to answer this question. As you will...

Our series of whole body vibration machine exercise articles continues...

Rebounding (an exercise technique involving jumping on a mini-trampoline) is...